28,000 Miles • 2 Years • 47 Countries

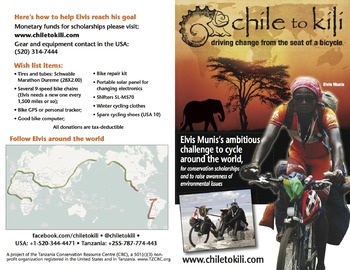

Meet Elvis Munis—he’s cycling around the world, unsupported, for two years to raise funds for education for fellow Tanzanian students in wildlife conservation.

In July, Elvis crossed into the U.S. from Mexico, and he's in Tucson, Arizona, right now giving presentations and talking to organizations about support for his cause. He'll be heading to the west coast in August, before heading north to Alaska and west to Russia and beyond.

Chile to Kili was conceived by the 25-year old Tanzanian student and naturalist after he identified one of the major conservation problems in his country: the lack of opportunity for Tanzanians to obtain the education necessary to manage their own natural resources.

The goal is to raise $100,000 as Elvis rides around thewold over the next two years – enough money for ten one-year conservation scholarships, and to support education at the Conservation Resource Centre (CRC).

Change must come from the inside.

Elvis left from Chile on January 1, 2012. He is riding, completely unsupported, around the world for 2 years in an effort to create opportunities for his fellow Tanzanians.

Chile to Kili: Driving change from the seat of a bicycle from ConserVentures on Vimeo.

Elvis is being the change he wants to see in the world.

What are you doing?

Meet Elvis in Tucson, Arizona this Thursday, July 26

Where: Summit Hut, 5045 East Speedway Boulevard Tucson, AZ 85712

(520) 325-1554 [Google Map]

When: 8 pm

What: Slide presentation and talk